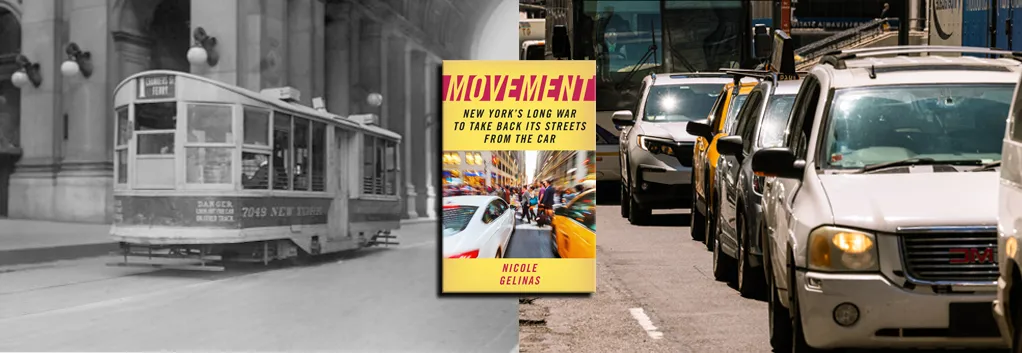

Movement: New York’s Long War to Take Back Its Streets from the Car

author’s corner q&A with Nicole Gelinas

by Ava Stryker-Robbins

Welcome to Author’s Corner, a new series by UrbanSense where we sit down with writers who are shaping conversation around cities, innovation, and the cultural currents of our time. From urban planners turned novelists to tech visionaries and culture entrepreneurs exploring the future of human connection, we'll learn from authors whose work captures the pulse of how we live, work, and plan the modern world. These are the voices helping us understand where we've been and where we're heading. Join us as we explore the stories behind the stories.

UrbanSense welcomes a diversity of viewpoints. Author’s views are their own and do not necessarily reflect any UrbanSense position.

About the author

Nicole Gelinas, senior fellow at Manhattan Institute, contributing editor at City Journal, and contributing writer at the New York Times, was recently awarded the 2025 Gotham Book Prize—an award given to authors of the best books written in or about New York City—for her recent book Movement: New York’s Long War to Take Back Its Streets from the Car.

This book, published by Fordham University Press, tells the story of how the car failed NYC and how essential NYC’s public transportation has been and will continue to be.

UrbanSense sat down with Nicole to learn more about her motivations for writing this book and how the history of transportation in New York has shaped how big ideas on policy and innovation can move forward.

"Like many global cities, though, New York had spent fifty years during the first half of the twentieth century trying and failing to tame its heavily populated landscape to fit the private automobile. New York has now spent more than fifty years trying to undo those mistakes, wrestling back city space for people, not cars."- Fordham University Press

Q: Why did you write Movement?

I started to be interested in transportation 25 years ago when I first moved to New York. I lived way out in South Brooklyn and had to take the F train for an hour each way to Ave. X. I started thinking on the ride, can't we improve this? Can’t we make this trip faster? I realized that you could really improve the quality of life for tens of thousands of people by shortening their commute by 20 minutes each way. So I started looking into the MTA and the MTA's finances and became more interested in transportation policy.

“Movement explores how, in the half-century leading up to the COVID- 19 pandemic, New York’s re-embracement of its mass-transit system and a livable streetscape helped save the city.”- Fordham University Press

Another big issue I became interested in was traffic deaths. When I lived on Ocean Parkway, two little girls were killed by a speeding, reckless driver who ran into them when they were sitting on a bench right in the median of the Parkway.

I thought this would cause outrage and would be on the front page of all the papers. I thought people would wonder how this city let this happen to these little girls and why the driver wasn’t going to prison for a long time? But it was just a tiny little news story.

That opened my eyes to the fact that we weren't thinking enough about how to reduce traffic deaths, even though you could save dozens or even hundreds of lives a year.

So over the years, I wrote about transit and policy for the New York Post and City Journal. I compiled stories, interviewed people, followed changes through the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations.

Naively, I thought I could write a chapter a month and be done with the book pretty quickly because I knew the stuff well. Of course, it ended up taking five years because you really learn what you don't know when you start writing. I interviewed a lot more people and tried to sort of make it a Book of Records.

Just as I looked up sources from 50-70 years ago and was grateful that other people had written about this before me, I hope that people 20-30 years from now who want to know more about New York City politics, history, culture, and how we got to the current physical landscape can look at this book to learn what was happening at this time.

Q: What did you learn from your writing process?

The main thing I learned has nothing to do with transportation or transit. It was most surprising to learn how long it takes to get anything done in New York City. I'm not talking about construction projects that have budget and overtime issues, I’m talking about civic movements that want to start out by getting rid of a road that goes through the park, building a bike lane, or setting up speed cameras. These are fairly simple. It doesn’t cost a lot of money to build a coalition of people who care about an issue, want to advocate for it, and want to find elected officials who will listen and cooperate. But it takes not years, but decades to get anything done in New York City. It requires a lot of patience and perseverance.

The governing establishment just banks on people giving up. They will try to weigh you out no matter what you are trying to do. So, as long as you don’t give up, you have survived ⅔ of the battle.

You know why Shirley Hayes got the road out of Washington Square Park? Because she would not give up even after 10 years of virtually everybody else giving up and being willing to compromise. So no matter what you’re working on, I think that’s a big insight that helps in understanding New York City politics.

The policy is not that hard. It’s getting the politicians to embrace the policy that is hard, and hopefully this book can serve as a blueprint on how to do that.

Shirley Hayes was a community activist in the 1950's most known for fighting to close Greenwich Village's Washington Square Park to traffic.

Q: What are your thoughts on how technology can improve the urban environment and transportation?

I'm not an anti-technology person and even if I were, there's not much I could do about it. But I think the city needs to be much clearer that we are in charge of technology and technology is not in charge of us.

The first technology to try to take over the streets was the car and it was very seductive. You can understand why people preferred to ride in their own car rather than sit crammed together on public transportation. The city tried to remake itself around the car and that really did not work out very well.

Then,15 years ago, with Uber and Lyft, things were not carefully scrutinized. We were getting people out of the subway and the buses. And that was not a good thing.

We have to be mindful of emerging technology like driverless cars. We need to be in charge of this technology. Otherwise, this city could find itself overrun by driverless cars.

Other examples of technology, like speed cameras, red light cameras, Wi-Fi connections so that the bus can keep the green light going, tapping to board instead of going through this cumbersome MetroCard process are perfectly good technologies. And again, we've been kind of slow to adopt some of them, but that's another case where we are using technology to our advantage rather than let the tech industry start to plan the city.

Related Content: UrbanSense Case study spotlight

Reducing Fare Evasion in the NYC Subway

UrbanSense partnered with the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice to understand the underlying issues leading to rising subway fare evasion.

Q: What are the most important takeaways from Movement?

I think the most important takeaway is that we're not stuck with the built environment that we inherited. For a long time, up until 10 years ago or so, if you were to suggest major changes like you constantly hear from elected officials today, you might think there's not a lot we can do about it. That you sort of have to just blame Moses, even though he hasn't had any power for close to 60 years.

So it's time that we take responsibility for our own built environment, and we've been doing that. We've taken back a lot of space from the car, certainly not enough, but we've proven that we can do it—you can take away a lane for bikes. And yes, lots of people will complain and continue to complain but you can do it and the world doesn't end.

On a much larger scale, we should finally think about what we want to do with the Cross Bronx Expressway. Do we want to put a cap with a park on top of it? It's not technologically all that difficult because a lot of it is a depressed roadway. It's just a matter of putting a deck on top of it and putting a park on that deck. It's just the political will to actually devote fiscal resources to this stuff. But I think by now we should just have no patience.

You can't keep blaming Robert Moses. We no longer live in Moses's world. We live in our own world.

“In 1969 master builder Robert Moses lost his long battle to urbanist Jane Jacobs over his planned Lower Manhattan Expressway. The ten-lane elevated expressway would have sliced across SoHo and Little Italy, demolishing historic buildings, and displacing thousands of families and businesses.”- Fordham University Press

discover more of Our Services

Policy Research & Analysis

Best practices, market insights, and data analysis to inform decisions and avoid common pitfalls.

Community engagement

In-depth user research, workshops, and surveys to co-create meaningful, user-driven solutions.

Economic Development

Delivering comprehensive economic development solutions that bridge technology, policy, and community needs.